The New Uncertainty About ‘Revenue’

With new accounting rules now in effect, income statement revenue may have little relationship to billing

By William H. Wiersema, CPA, Principal, Miller, Cooper & Co., Ltd.

New revenue recognition rules in accounting became effective for Dec. 31, 2019, year ends. The most significant change is recording it “Over Time” (OT), meaning during production or projects, rather than when done. OT matches revenue pro-rata with production or project progress. The idea is to recognize profit contemporaneously as earned along with its associated costs. Companies avoid the lumpiness of recognizing revenue under other methods.

However, in doing so, OT accelerates income and increases net assets compared to prior accounting. Profits come earlier compared to waiting until completion or shipment. Rather than defer revenue until done, the new method draws upon interim estimates, without historical facts. Inevitably, assessments must be trued-up in future accounting periods.

For example, a manufacturer might need three months to produce a custom item. It would traditionally carry deposits collected from the customer on its balance sheet as liabilities while accumulating material, labor, and overhead costs as a work-in-process asset. Only at shipment would these accounts close out to the income statement.

Under the new OT, however, that manufacturer writes off costs as incurred and records revenue based on the share of a project completed. Effectively at each accounting period, profit is added to inventory costs, in a way resembling unbilled accounts receivable.

This article intends to sort out and highlight the issues involved, including pitfalls going forward, to give readers a better perspective.

Redefine revenue

Previously, sales revenue, the income statement top line, equaled billings to customers upon shipment of products. Service companies also billed and recorded revenue as projects closed. Even when companies issued progress billings, sales were triggered only by shipment or completion, with related costs and customer deposits parked on the balance sheet until then. OT applied to long-term construction contracts, not to outputs of standard manufacturing processes.

Since the change, income statement revenue may have little relationship to billing. Under new practices, companies must consider OT before any other option. Any of the following criteria trigger OT:

- The customer consumes the products or services as delivered: Examples include periodic maintenance and “stand-ready obligations” for services on demand, such as website or facility access.

- The customer controls the asset as the vendor improves it: OT applies to improvements to a computer network equally to constructing a building on a customer’s land. Considerations in control include title, right to payment, physical possession, customer acceptance, and ownership risks.

- The customer owes the vendor for a custom in-process item’s sales value, not simply costs, and the item has no alternate use to the vendor: An example is a fixed-fee arrangement that reimburses work at standard billing rates if the customer cancels. Many types of contracts, including those for federal supply, explicitly contain these terms. OT does not apply where the vendor must mitigate damages by offering the item for sale to others.

OT treatment for custom manufacturing “to order” or services is not automatic. As a practical matter, companies under short lead times without progress payments fall outside OT rules. If OT does not apply, custom-manufactured items generate revenue when shipped, at delivery, or only after installed and accepted by the customer, depending on when control transfers.

Apply OT

Once a company has contracts that are subject to OT, the next step is applying it. The minimum information necessary includes contract price and a progress measure that reflects the transfer of value. Expenses pass directly to the income statement, rather than be carried as assets.

OT allows tracking progress in various ways but under rigorous restrictions. Each business must justify its choice. As to measuring progress, companies generally use cost-to-cost, which compares the cost incurred to date to the total budget.

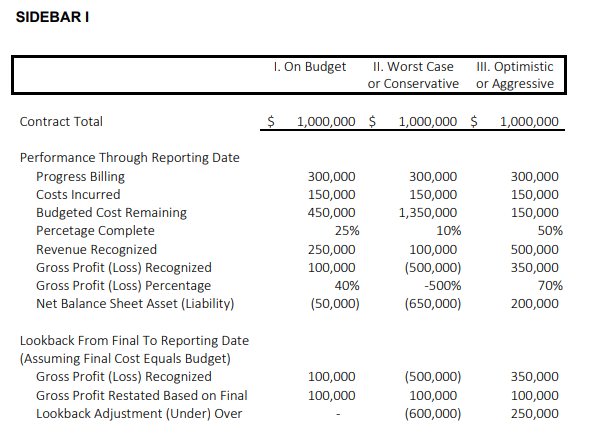

The sidebar contains scenarios that illustrate the method’s substantial impact. After incurring $150,000 of a budgeted $600,000 in costs, a manufacturer must determine its revenue and profit. Although no revenue or profit would be recorded under prior practices, under the new rules, if done at budget, revenue is $250,000 and gross profit $100,000.

When viewed conservatively in Scenario II, revenue falls to $100,000, and a $500,000 loss is incurred. When remaining costs are estimated more aggressively in Scenario III, revenue grows to $500,000, or one-half of the contract price, and gross profit escalates to $350,000.

The illustration assumes cost-to-cost. However, companies must consider other approaches to the degree that they better reflect value transfer. Progress is based on inputs, such as direct labor time incurred, or on outputs, such as products completed. Other measures include hours, units, appraisals, or ratable across periods. The quantity incurred to date comprises progress relative to budget.

One shortcut adds a markup to costs incurred without computing the remaining budget. It seems more straightforward and defers having to develop an estimating system. For example, a 40% gross profit applied to $150,000 costs implies $250,000 in revenue. The computation is $150,000 divided by 60%, which equates to one minus the 40% margin. Even simpler, but least likely accurate, is to guesstimate a percentage complete and multiply it by the total contract price.

The difference between revenue recognized and progress billings becomes an asset or liability on the balance sheet. When the difference results in an asset, the work’s value exceeds what’s been billed. Underbilling naturally raises eyebrows for financial statement users such as lenders. However, if it’s a liability, the progress billing exceeds the work-in-process’ sales value, which make users more comfortable.

Beware of estimates

Not surprisingly, lenders or other financial statement users are unhappy when estimates are substantially off from actual. Differences also have a dollar-for-dollar impact on the value of a business that changes ownership.

Typically, the over- and under-billing items are reimbursed between buyer and seller. However, the final results are not known until all production and projects are completed.

The method can be manipulated. Fraud authority Howard Schilit, in his book Financial Shenanigans, characterizes OT as “an aggressive accounting practice that can overstate earnings.” He considers two major problems: “First, this method relies on estimates of future costs and future events; it can therefore be manipulated by distorting cost estimates or stage-of-completion records. Second, changes in estimates may be motivated more by a desire to control reported profits than by new information.” He cites the example of a start-up company that reported profits based on the method that had to be reversed when it failed to complete the related long-term projects.

Intentional misstatement aside, no accounting can overcome the fact that budgeted quantities never exactly equal the actual. Assessing information requires a look back from final results to interim estimate. At the foot of the sidebar, the look back compares actual performance to the reporting period to determine how much misstatement occurred. The conservative Scenario II understated gross profit at quarter-end by $500,000. The optimistic Scenario III, however, overstated profit by $250,000. Results would be disclosed in the financial statement.

The new OT rules control potential errors by mandating pro-rata earnings across the performance obligation, without front- or back-loading. Adjustments remove costs unrelated to satisfying performance obligations. For example, using a progress measure keeps an initial deposit from being revenue. Additionally, incremental up-front costs, such as for obtaining or setting-up customers, are disregarded. Charging a non-refundable set-up fee, such as for initiating a service, is irrelevant.

Companies with work-in-process cannot use output measures, such as units completed or milestones. Production costs exclude uninstalled materials and inefficiency. Where raw materials are purchased at the beginning of a project and not custom-designed, they should either be left as work-in-process on the balance sheet, or recorded as revenue at no profit, if control transfers to the customer. Likewise, issuing materials carried in stock generates no revenue recognition until customized.

On the other hand, OT includes design and learning costs incurred early in a contract for custom items, because pricing decreases with volume. Parts purchased from third parties but designed by the company are also includable in progress measures. Unlike other types of initial costs, they directly satisfy performance obligations.

Many companies have inadequate estimating and cost tracking. Complying with the new rules might take replacing the accounting system. Prior literature required reliable estimates of progress to use OT; otherwise, companies had to wait until project completion. On the other hand, companies who lack the data today presumably could not issue financial reports under Generally Accepted Accounting Principles. Under the new rules, companies avoid OT only when a project’s nature makes it inestimable.

The hope with the new rules is in bringing uniformity of accounting practices across industries and around the world. Facing them, many companies must give it their best shot and hope it turns out.

Example of revenue recognized ‘over time’

In the example below, a manufacturer has a $1 million contract to produce custom items. In fulfilling the order, the manufacturer expects costs of $600,000 for a gross profit of $400,000 or 40%. At the time of its quarterly financial statements, the company billed $300,000 and incurred $150,000 in costs. Traditionally, activity through this interim date would not be reflected on the income statement, just the balance sheet. The $300,000 collected would be a customer deposit liability, and the $150,000 in costs as work-in-process.

However, under the new revenue recognition rules, income accretes as the project progresses, based on estimates. As indicated below, significant differences in revenue and profit can occur as production progresses. Adjustments to actual performance occur in the period that the amounts become known, not back to the estimated period.

Three scenarios are illustrated:

- Scenario I, On Budget: Although the case would never happen in real life, performance exactly at budget provides a baseline for comparison to the other two scenarios. Because costs incurred are 25% of the total estimate, that share of the $1 million price, or $250,000, is recognized as revenue. When compared to $150,000 in costs, this results in the budgeted 40% gross profit margin.

- Scenario II, Worst Case, or Conservative: Here, on the other hand, the estimator foresees significant problems with the project causing additional costs not recoverable from the customer. The estimated total costs are $1.5 million, which would result in a $500,000 loss. Under revenue recognition rules, this loss must be recognized in full immediately.

- Scenario III, Optimistic, or Aggressive: Management is overly optimistic that they can outdo their estimates and achieve a final cost of only $300,000, for a 70% gross profit margin. As such, the completion percentage elevates to 50%, with $500,000 revenue recognized. Net assets of $200,000 appears on the balance sheet compared to the net liabilities of the first and second scenarios.

CREDIT:

Reprinted with permission from the October 2020 issue of Electrical Apparatus magazine